03 Jan Arabic Etymology: From Zero to Zenith 27th November 2015

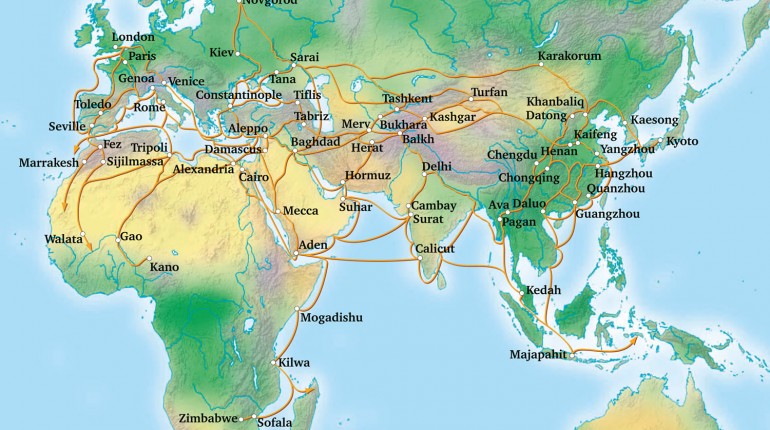

For over a thousand years, Arab merchants plied trade routes that criss-crossed the known world, by sea and caravan, connecting Timbuktu to India, Italy and Zanzibar, trading in scents, textiles, spices and – the most valuable commodity of all – knowledge. Languages as disparate as English, Turkish, Spanish, Farsi, Italian, Hindi, French, Somali, Portuguese and Swahili all bear words of Arabic origin. How many of us would have guessed that the words ‘cotton’, ‘average’, and even ‘gibberish’ come from Arabic?

Echoes of Arabia

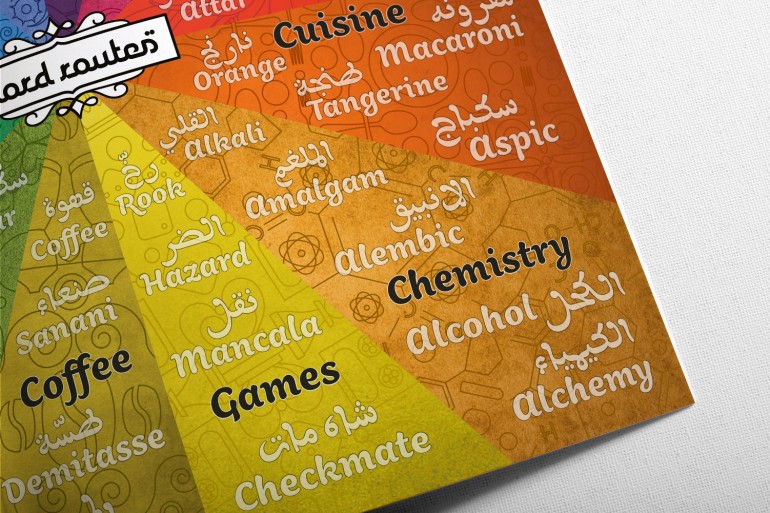

To help bring some of this fascinating knowledge to members of Aramco Overseas Company’s staff, who are of diverse backgrounds but may use words derived from Arabic every day without realising, we created a diary for Aramco Overseas called ‘Echoes of Arabia: Arabic Roots of Everyday English’.

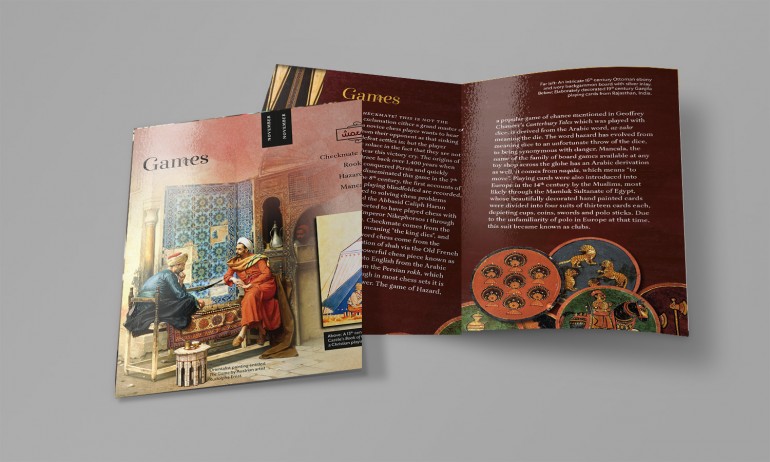

Twelve striking fold-out dividers explore themes from aromatics to games in this pocket-sized Filofax-style diary, protected by an understated blue suede cover. Our specialist researchers compiled detailed ‘word routes’, accompanied throughout by specially crafted Arabic typography, showing the ways by which Arabic words have historically travelled the world and are alive today in our conversations.

When scientific breakthroughs travelled from the Arab world to the West their names went with them. Terms used in chemistry (alchemy, alcohol, alkali…), mathematics (algorithm, nadir, algebra…), music (lute, guitar, troubadour), among many other fields, also come from from Arabic. Roman numerals did not even have a concept for zero until Arabs introduced it (hence ‘cipher’, from ‘sifr’), while Arab scholars brought everything from positive and negative numerals, the theory of atoms and hundreds of stars to the awareness of the West.

Powerful Pens

Although the origins of Arabic writing go back via Ancient Phoenician to cuneiform, the Babylonian system of making marks in wet clay, it was not until the revelation of the Qur’an and the need to produce copies of it that writing became a critical concern for Arabs. Initially written on animal bones and leather, with the discovery of papermaking – the first paper factory in Europe was built in Xátiva in Islamic Spain – books in Arabic could be reproduced at a phenomenal pace.

And they were in high demand: at the peak of its sophistication, around 1000 CE, Cordoba in Spain boasted five private libraries with over a quarter of a million volumes each. Workshops of scribes worked furiously to copy books that could be sent from one side of the Islamic world to the other, reaching Cairo, for instance, in a matter of months. There was even a special kind of lightweight paper that was developed for use with carrier pigeons: to prepare for a lunar eclipse in 997 CE, the astronomers Al-Biruni and Abu’l-Wafa maintained a carrier pigeon correspondence between what is now Afghanistan and Baghdad.

Many of these books were translations of Ancient Greek texts which were forbidden in the rest of medieval Europe; however one open-minded ruler, Raymond of Toledo, not only allowed the texts into his scholarly court but funded their translation into Latin. Students from all over Europe came to Toledo to study, eventually bringing the knowledge they learned there back to their native countries.

As the calendar section on Spain reveals, medieval works on medicine, astronomy, botany, agriculture, philosophy and many other sciences first entered Europe by way of Hispanic Arabic, contributing pivotally to the Enlightenment.

Silks, Spices and A Game of Chess

But this was not the only way that Arabic words made their way into other languages. Trade meant the necessity of communication, and all along the Silk and Spice routes Arabic was a lingua franca that traders of all different backgrounds used in common. The products themselves usually dictated a new (albeit slightly evolved) word in the host languages – hence the concept of ‘word routes’ that we developed throughout the calendar.

Sailors from North Africa arriving in Italian ports such as Genoa brought new products such as cotton (from ‘al-qutn’), damask (from the city name ‘dimashq’), sashes (sash) and sequins (sikka). One could enjoy a game of chess (from the Arabic ‘ash-shatranj’, itself from the Persian ‘shatrang’) while sitting comfortably on a sofa (‘suffah’) and enjoying a cup of tea (‘shay’). It was also around this time that the word ‘carat’ entered Latin from the Arabic term ‘qirat’, meaning one-twenty-fourth of the medieval gold dinar.

Delicious Dishes and Little Luxuries

Food was, of course, one of the best ways for Arabic words to get about, since the Arabs would typically bring seeds and plants with them as wherever they settled to be able to make their favourites dishes. Thanks to them we have sugar (from ‘as-sukkar’), saffron (from ‘az-zafran’), pistachio (‘fistash’), lemon (‘limun’), apricot (‘al-barquq’), carob (‘al-kharrub’), aubergine (badinjan), spinach (‘isfanakh’), artichoke (‘al-kharshuf’) and more recently, that picnic favourite ‘hummus’. So important is coffee (‘al-qahwa’) to Arabs and westerners alike that it has its own section in the Aramco World calendar.

If that wasn’t enough to delight the senses, jasmine, musk, amber, sandalwood, loofahs, kohl and mascara all entered our cupboards and our dictionaries from Arabic. We dedicated the month of July to the Spa, recognising the importance of the Arab hammam to the modern lifestyle. We even owe the word massage (from ‘mass’, to touch or knead) to Arabic!

In Search of Lost Words

The Oxford English Dictionary records over 900 words of Arabic origin, many of which are so rooted in our language that we have no clue as to their exotic origins. Aramco Overseas Company was delighted with the finished product which, with our specialism and attention to detail, as well as a quick turnaround, conveys the little-known etymology of hundreds of English words of Arabic origin in a beautiful and original keepsake.